The Cartesian method applied to redefining our brand identity

“I think, therefore I am,” Descartes wrote in the Discourse on the Method. Brilliant, he continued in the Meditations on First Philosophy, “But I do not yet know with sufficient clearness what I am, though assured that I am.”

As an organisation, you know that you are (let’s leave Shakespeare out of this, shall we?), but do you know what exactly you are? Do you really understand your own identity? Or even, are you still in tune with the one you’ve once defined and still portray?

You may have undertaken this exercise before. Possibly more than once. And you’ve asked yourself a thousand questions. Where do we start? How do we proceed? What exactly are we trying to clarify? Should we schedule a meeting? Does 9:30 work for everyone? Shall we grab a coffee?

We’ve been there too. Cartoonbase has done this exercise five times according to the authorities. Eleven according to the protesters.

Last time we took it on, we decided to try something different and invite Descartes to the table.

Here’s how.

Contents

- 1 The four rules of the method

- 2 Portrait

- 2.1 Rule #1: “never accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such.”

- 2.2 Rule #2: “divide each of the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and as might be necessary for its adequate solution.”

- 2.3 Rule #3: “conduct my thoughts in such order that, by commencing with objects the simplest and easiest to know, I might ascend by little and little, and, as it were, step by step, to the knowledge of the more complex.”

- 2.4 Rule #4: “make enumerations so complete, and reviews so general, that I might be assured that nothing was omitted”

- 3 We are…

The four rules of the method

In the Discourse on the Method (1637), Descartes outlines a series of rules for producing true reasoning. Truth, for Descartes, is what is clear and distinct, what possesses the character of obviousness. Conversely, error resides in the obscure, the mixed, and the confusing.

Four rules allow for true reasoning:

- The rule of evidence: “never accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such.”

- The rule of analysis: “divide each of the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and as might be necessary for its adequate solution.”

- The rule of deduction: “conduct my thoughts in such order that, by commencing with objects the simplest and easiest to know, I might ascend by little and little, and, as it were, step by step, to the knowledge of the more complex.”

- The rule of enumeration: “make enumerations so complete, and reviews so general, that I might be assured that nothing was omitted.”

In other words, instead of taking a statement at face value, Descartes invites us to question it, break it into simpler elements, reconstruct a chain of meaning from these simpler elements, and once that chain is complete, ensure that nothing has been overlooked.

This is the method we applied to the (re-)definition of our identity. Our goal: to draw a portrait that resembles us, one that is truly us, because it has the character of obviousness.

Portrait

Rule #1: “never accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such.”

The content department found it very irritating that we were talking about ourselves in so many ways. The sales department felt it was essential that we had different elements of language for every situation. As for management, they thought it was perfectly normal for the company to evolve, and therefore for its way of presenting itself to evolve too. In their view, it is essential for an organisation to constantly adapt to its environment. And it is at least as essential to take a step back, from time to time, to redefine the brand’s personality. (Yes, they’re pretty good at this.)

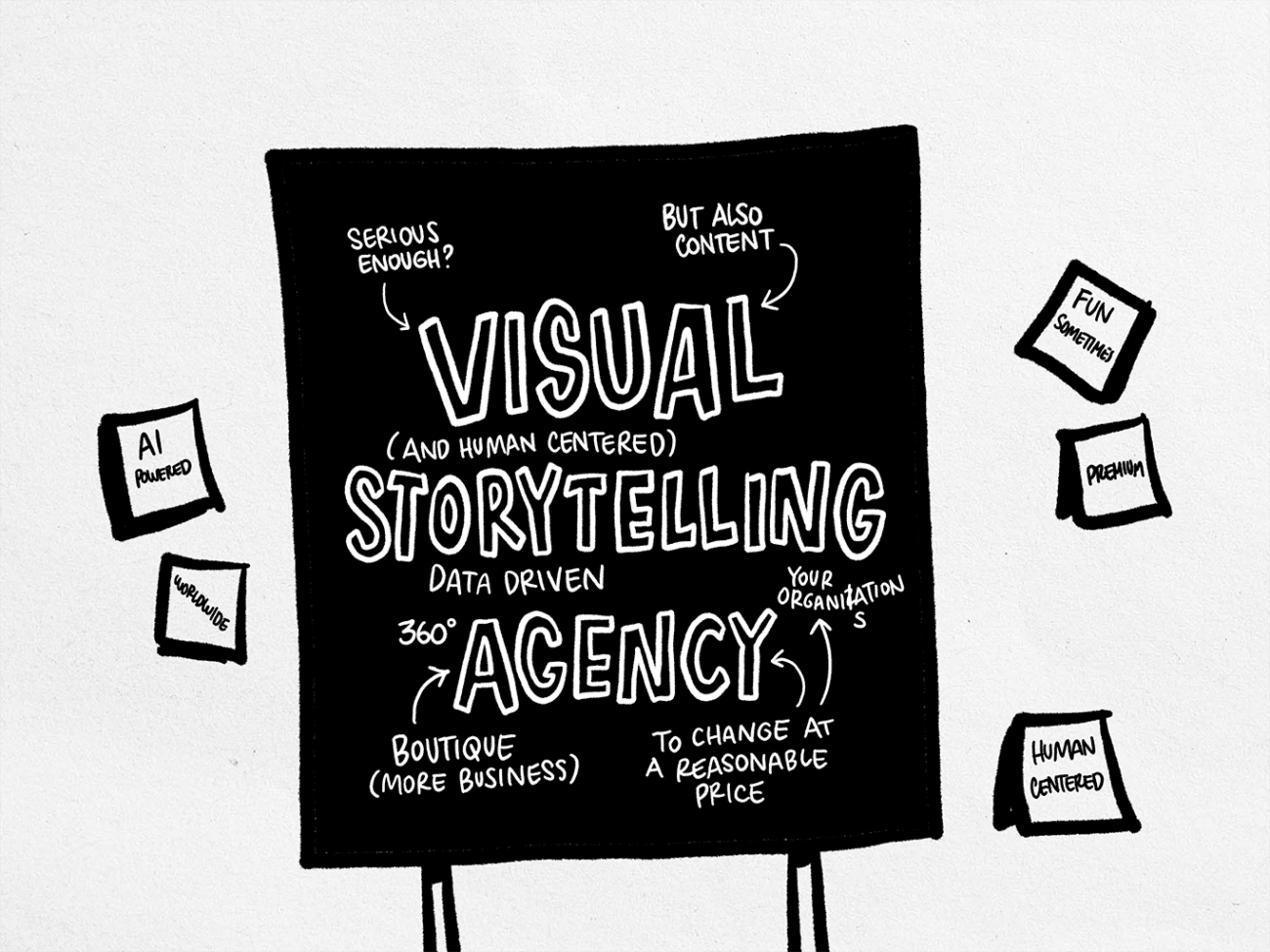

We started by gathering information about us—from our website, in our presentations, our pitches. And we found many, many things.

From all the elements of language we gathered, we sensed that not everything should be discarded. But we couldn’t work out what criteria to use to decide which ones should stay. What we lacked was a core to string these elements together; an underlying chain of meaning we could extract them from. What we lacked was a story.

Rule #2: “divide each of the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and as might be necessary for its adequate solution.”

So we decided to reverse-engineer the problem. Rather than proceeding from the result (the elements of language) back to a core, we decided to build a narrative first, hoping to be able to deduce from it the statements we needed. To do so, we “divided” our quest for identity into “parts” or simple elements, which we conceived as a series of questions.

- Who are we?

- What do we do?

- Whom do we do it for?

- Why do we do it?

- How do we achieve it?

- What makes us unique?

- What do we believe in?

One meeting followed another as we answered question after question.

Then we got stuck, exactly midway, as we were tackling the “why?”.

Our answers to the question “Why do we do what we do?” were pulling in different directions. Applying a little rigour to our thoughts, we came to realise that the problem lay in the double meaning of “why?”. When you think of it, any question starting with “why?” can have at least two different types of answers. Some will start with “Because…” and point to an origin, a reason. Others will begin with “To…” and indicate a destination, an end goal. So we decided to avoid using “why?” and split question 4 into two parts that became questions 4 and 5.

- What are we trying to achieve?

- What is the reason we want to achieve it?

- How do we achieve it?

- What makes us unique?

- What do we believe in?

We went about answering these questions with one constraint: to try and avoid repetition as much as possible. Once an idea fell into a question category, it could no longer be used elsewhere. This constraint proved extremely helpful. It helped us give consistency to our story. And it forced us to look further afield when we were out of material, acting as a driving force for creativity.

The process was challenging, but the more we progressed, the easier it got. Questions 6, 7, and 8 were a lot quicker to answer than the previous ones. Because the story, by then, was actually already clear.

Rule #3: “conduct my thoughts in such order that, by commencing with objects the simplest and easiest to know, I might ascend by little and little, and, as it were, step by step, to the knowledge of the more complex.”

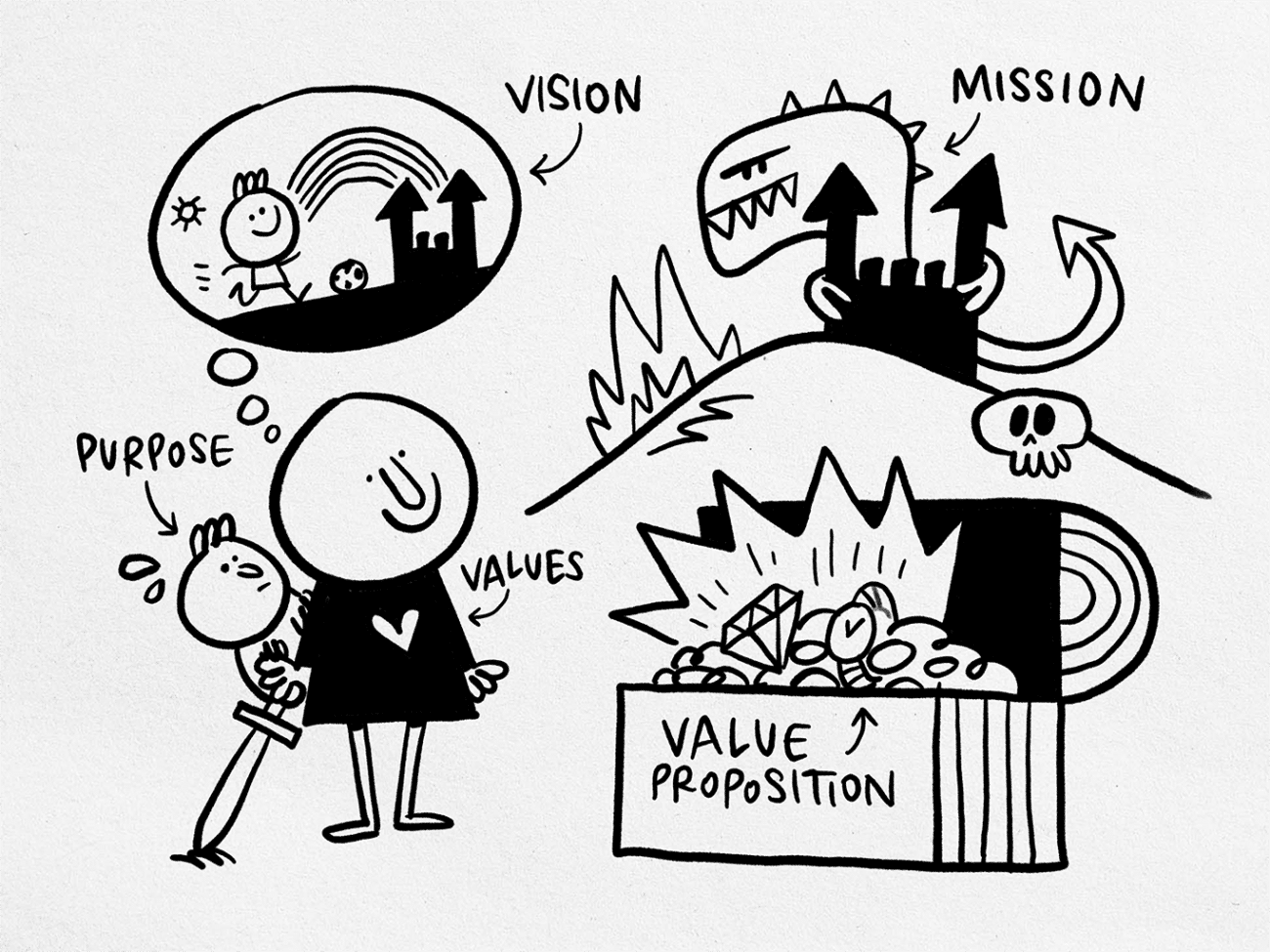

From the answers to these simple elements, these “parts,” we built a consistent narrative.

And it is this narrative we used as a basis to formulate the mission, vision, value proposition, and values statements. It is this framework we relied on to lend solidity and credibility to the wording that would define our identity. At this stage, all that was left to do was a copywriting exercise.

- We drew the mission from points 2 and 6

- The vision from point 4

- The purpose from point 5

- The value proposition from point 7

- And the values themselves from point 8

Rule #4: “make enumerations so complete, and reviews so general, that I might be assured that nothing was omitted”

From the narrative we built and the statements we formulated, we were also able to deduce a wealth of elements that would shape the identity of our brand :

- Various lengths of written material presenting our brand, with a tag line, a boilerplate, and an elevator pitch.

- Personality traits informing our tone of voice and copywriting guidelines

- Text for several sections of our website, including About us, Our approach, Our Roadmap…

Were we certain, at the end of this exercise, that we had not omitted anything? Not quite. But again, it’s only fair circumstances require that we reposition ourselves. When this is the case, when we need to pitch Cartoonbase from a different angle, in a different length, with a different format, we make sure we come back to the core, to the story of our brand.

We are…

Would we have got to a different result had we not based our reasoning on Descartes? Probably not. Telling stories is our trade. There’s no reason why we wouldn’t apply it to ourselves too.

However, following the rules set out by Descartes certainly helped us clarify our thoughts, and add some rigour to our reasoning.

Do we now all agree that this exercise is done, once and for all? No we don’t. Management, copy, marketing, and sales are still grappling over a comma as this article is being published.

No one knows where this punctuation battle will take us.

But the process was certainly worth the effort.